Mole Concept Stoichiometry and Behavior of Gases

Mole Concept Stoichiometry and Behavior of Gases Synopsis

Synopsis

Mole Concept

A mole is a collection of 6.022 × 1023 particles.

A mole is the amount of a substance containing elementary particles like atoms, molecules or ions in 12 gram of carbon-12 (12C).

Avogadro’s Number

It is the number of atoms present in 12 gram of C-12 isotope, i.e. 6·023 × 1023 atoms.

It is denoted by NA or L.

NA = 6·023 × 1023

1 mole of atoms = 6·023 × 1023 atoms

1 mole of molecules = 6·023 × 1023 molecules

1 mole of electrons = 6·023 × 1023 electrons

1 mole of a gas = 22·4 litre at STP

Applications of Avogadro’s Law

- It explains Gay-Lussac’s law.

- It determines atomicity of the gases.

- It determines the molecular formula of a gas.

- It determines the relation between molecular mass and vapour density.

- It gives the relationship between gram molecular mass and gram molar volume.

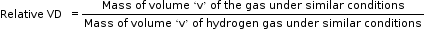

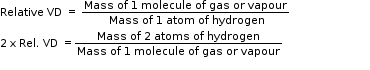

Relative Vapour Density (VD)

Relative vapour density is the ratio between the masses of equal volumes of a gas (or vapour) and hydrogen under the same conditions of temperature and pressure.

According to Avogadro’s law, volumes at the same temperature and pressure may be substituted by molecules.

Hence,

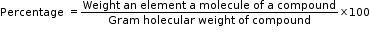

- Percentage Composition

The percentage by weight of each element present in a compound is called percentage composition of the compound.

- Empirical Formula

It is the chemical formula which gives the simplest ratio in whole numbers of atoms of different elements present in one molecule of the compound. - Empirical Formula Mass

It is the sum of atomic masses of various elements present in the empirical formula.

Empirical Formula Weight (EFW)

The empirical formula weight is the atomic masses of the elements present in the empirical formula.

EFW of H2O2=2 × (H) + 2 × (0)

=2 × 1 + 2 × 16

=34 amu - Molecular Formula

It denotes the actual number of atoms of different elements present in one molecule of the compound.

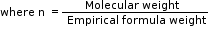

Molecular formula = Empirical formula × n

Examples: Molecular formula of

Zinc nitrate: Zn(NO3)2

Butane: C4H10

Glucose: C6H12O6

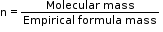

Relationship between empirical formula and molecular formula

Molecular formula = Empirical formula × n

where ‘n’ is a positive whole number

- Chemical Equation

A shorthand notation of describing an actual chemical reaction in terms of symbols and formulae along with the number of atoms and molecules of the reactants and products is called a chemical equation.

A chemical equation is a balanced account of a chemical transaction.

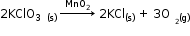

- Molecular proportion of a substance

In the above reaction, 2 molecules of solid KClO3 on heating in the presence of MnO2 produce 2 molecules of solid KCl and 3 molecules of O2(g). - Relative weights of substances

2 × 122.5g = 245 g of potassium chlorate - Volumes of gaseous substances

3 × 22.4 L = 67.2 L of oxygen at STP is evolved when 245 g of potassium chlorate is heated.

- A symbol represents a short form of an element.

- A symbol represents one atom of the element.

- It indicates the atomic weight of an element. The quantity of the element is equal to its atomic mass, gram atomic mass or atomic mass unit (amu).

For example, the symbol C

- Stands for the element Carbon

- Represents one atom of Carbon

- Indicates the atomic mass of Carbon, i.e. 12 amu

- In most cases, the first letter of the name of an element was taken as the symbol for that element and written in capitals.

- In some cases, the initial letter of the name in capital along with its second letter in small was used.

- Symbols for some elements were derived from their Latin names.

- Symbols of elements used today are those as first suggested by the Swedish chemist Berzelius.

- The method suggested by Berzelius forms the basis of the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) system of chemical symbols and formulae.

- The names and symbols decided by IUPAC are used all over the world for international trade.

- Monovalent electropositive ions

Ammonium NH4+

Cuprous Cu+

Mercurous Hg+ - Bivalent electropositive ions

Argentic Ag2+

Ferrous Fe2+

Stannous Sn2+

Cupric Cu2+ - Trivalent electropositive ions

Aluminium Al3+

Chromium Cr3+

Arsenic As3+ - Tetra positive ions

Plumbic Pb4+

Stannic Sn4+

- Monovalent electronegative ions

Acetate CH3COO− Permanganate MnO4−

Bisulphite HSO3− Cyanide CN−

Bisulphate HSO4− Hypochlorite ClO− - Bivalent electronegative ions

Carbonate CO32− Silicate SiO32−

Oxide O2− Chromate CrO42−

Sulphate SO42− Oxalate (COO)22− - Trivalent electronegative ions

Arsenate AsO43−

Phosphide P3−

Phosphate PO43−

Borate BO3- - Tetravalent electronegative ions

Carbide C4−

Ferro cyanide [Fe(CN)6]4−

- The name of the substance.

- Both molecule and molecular mass of the compound.

- The respective numbers of different atoms present in one molecule of a compound.

- The ratios of the respective masses of the elements present in the compound.

- CO2 represents carbon dioxide.

- The molecular formula of carbon dioxide is CO2.

- Each molecule contains one carbon atom joined by chemical bonds with two oxygen atoms.

- The molecular mass of carbon dioxide is 44, given that the atomic mass of carbon is 12 and that of oxygen is 16.

- Binary acids

The names of binary acids are given by adding the prefix hydro– and the suffix –ic to the name of the second element.

Example: HCl – Hydrochloric acid

HF – Hydrofluoric acid - Acids containing radicals of polyatomic groups

The names of acids containing radicals of polyatomic groups such as sulphate SO4, nitrate NO3 etc. are given on the basis of the second element present in the molecule, and the prefix hydro– is not used.

Example: H2SO4: The second element is sulphur; thus, the name sulphuric acid.

HNO3: The second atom is nitrogen; thus, the name nitric acid.

- Gases consist of a large number of minute identical particles (atoms or molecules) which are very small.

- Gas molecules are so far apart from each other that the actual volume of the molecules is negligible as compared to the total volume of the gas. They are thus considered point masses.

- There is no force of attraction between the particles of a gas at ordinary temperature and pressure.

- Particles of a gas are always in constant and random motion.

- Particles of a gas move in all possible directions in straight lines. During their random motion, they collide with each other and with the walls of the container. Pressure is exerted by the gas as a result of collision of the particles with the walls of the container.

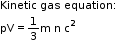

- Collisions of gas molecules are perfectly elastic, i.e. the total energy of molecules before and after the collision remains the same. Although energy is exchanged between colliding molecules, their individual energies may change, but the sum of their energies will remain constant.

- At any particular time, different particles in the gas have different speeds and hence different kinetic energies.

- In kinetic theory, it is assumed that the average kinetic energy of the gas molecules is directly proportional to the absolute temperature.

- Gases show deviation from ideal behaviour because of two faulty assumptions:

- There is no force of attraction between the molecules of a gas.

- Volume of the molecules of a gas is negligibly small compared to the space occupied by the gas.

- At low temperature and high pressure, gases deviate from ideal behaviour, i.e. gases behave as real gases.

- At low pressure and high temperature, gases show ideal behaviour, i.e. gases behave as ideal gases.

- Gases which are soluble in water are easily liquefiable, i.e. gases such as CO2, SO2 and NH3 show larger deviations than gases such as H2, O2 and N2.

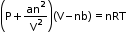

- Van der Waals equation of state:

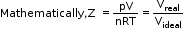

where a and b are Van der Waals constants, and n is the number of moles of the gas. - The deviation from ideal behaviour can be measured in terms of the compressibility factor Z, which is the ratio of the product of pV and nRT.

For ideal gas: Z = 1

For real gas: If Z < 1, it is called negative deviation.

If Z > 1, it is called positive deviation. - Compressibility factor (Z) versus pressure (p) for some gases:

- Deviations from ideal behaviour decrease with an increase in temperature.

- The temperature at which a real gas obeys the ideal gas law over an appreciable range of pressure is called Boyle temperature or Boyle point.

- The behaviour of a gas under known conditions of temperature, pressure and volume is described by laws known as gas laws.

- The standard variables used for gas laws are pressure (P), temperature (T) and volume (V).

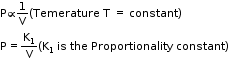

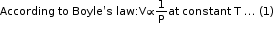

- At constant temperature, the volume of a given mass of a dry gas is inversely proportional to its pressure.

Hence, PV= K1=Constant - Boyle's law can also be stated as ‘for a given mass of a gas the product of pressure and volume is always constant at constant temperature’.

- If P1, P2 and P3 are the pressures of the given masses of a gas and V1, V2 and V3 are the volumes at constant temperature, then according to Boyle’s law:

P1V1=P2V2=P3V3=K1= Constant

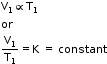

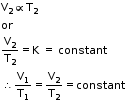

- Charles’s Law

- At constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of a dry gas increases or decreases by

of its original volume at 0°C for each degree centigrade rise or fall in temperature.

of its original volume at 0°C for each degree centigrade rise or fall in temperature.

V ∝ T (at Constant Pressure) - At temperature T1 (K) and volume V1 (cm3),

- At temperature T2 (K), volume is V2 (cm3).

or V = kT

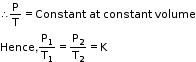

or V = kT- The French chemist and physicist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac made several observations on variation of pressure of a gas with temperature.

- At constant volume, the pressure of a given mass of a gas increases or decreases by

of its pressure at 0°C for every 1°C rise or fall in temperature.

of its pressure at 0°C for every 1°C rise or fall in temperature. , i.e. P = kT

, i.e. P = kT

- Pressure versus temperature (Kelvin) graph at constant molar volume.

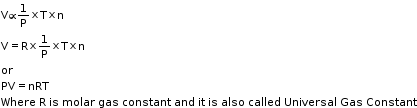

Avogadro Law (Volume–Amount Relationship)

- In 1811, the Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro proposed that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure should contain equal number of molecules.

- A gas which follows Boyle’s law, Charles’ law and Avogadro’s law strictly is called an ideal gas.

- It is an imaginary gas which has 0 volume at 0 K.

- The gas equation is an equation used in chemical equations for calculating the changes in volume of gases when pressure and temperature both undergo a change, thereby giving a simultaneous effect of changes of temperature and pressure on the volume of a given mass of a dry gas.

- Different values of the universal gas constant:

R = 8.314 Pa m3 K−1 mol−1

= 8.314 × 10−2 bar L K−1 mol−1

= 8.314 J K−1 mol−1 - If the volume of a given mass of a gas changes from V1 to V2, its pressure changes from P1 to P2 and its temperature changes from T1 to T2, then

The above equation is called the gas equation. This equation is also called the combined gas equation.

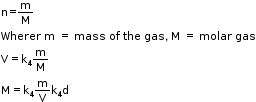

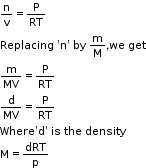

Density and Molar Mass of a Gaseous Substance - Ideal gas equation can be rearranged as follows:

- According to Dalton’s law of partial pressures, the total pressure exerted by the mixture of non-reactive gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of individual gases.

Mathematically, it is written as

ptotal = p1 + p2 + p3

ptotal is the pressure exerted by the mixture of gases

where p1 + p2 + p3 are partial pressures of gases - Pressure of a dry gas is calculated as

pDry gas = ptotal − Aqueous tension - Pressure exerted by saturated water vapour is called aqueous tension.

- Partial pressure in terms of mole fraction is expressed as

pi = xi × ptotal

where pi is partial pressure of ith gas and xi is the mole fraction of ith gas.